- Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os X

- Mac Os Catalina

- Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os Catalina

- Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os 8

- Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os Download

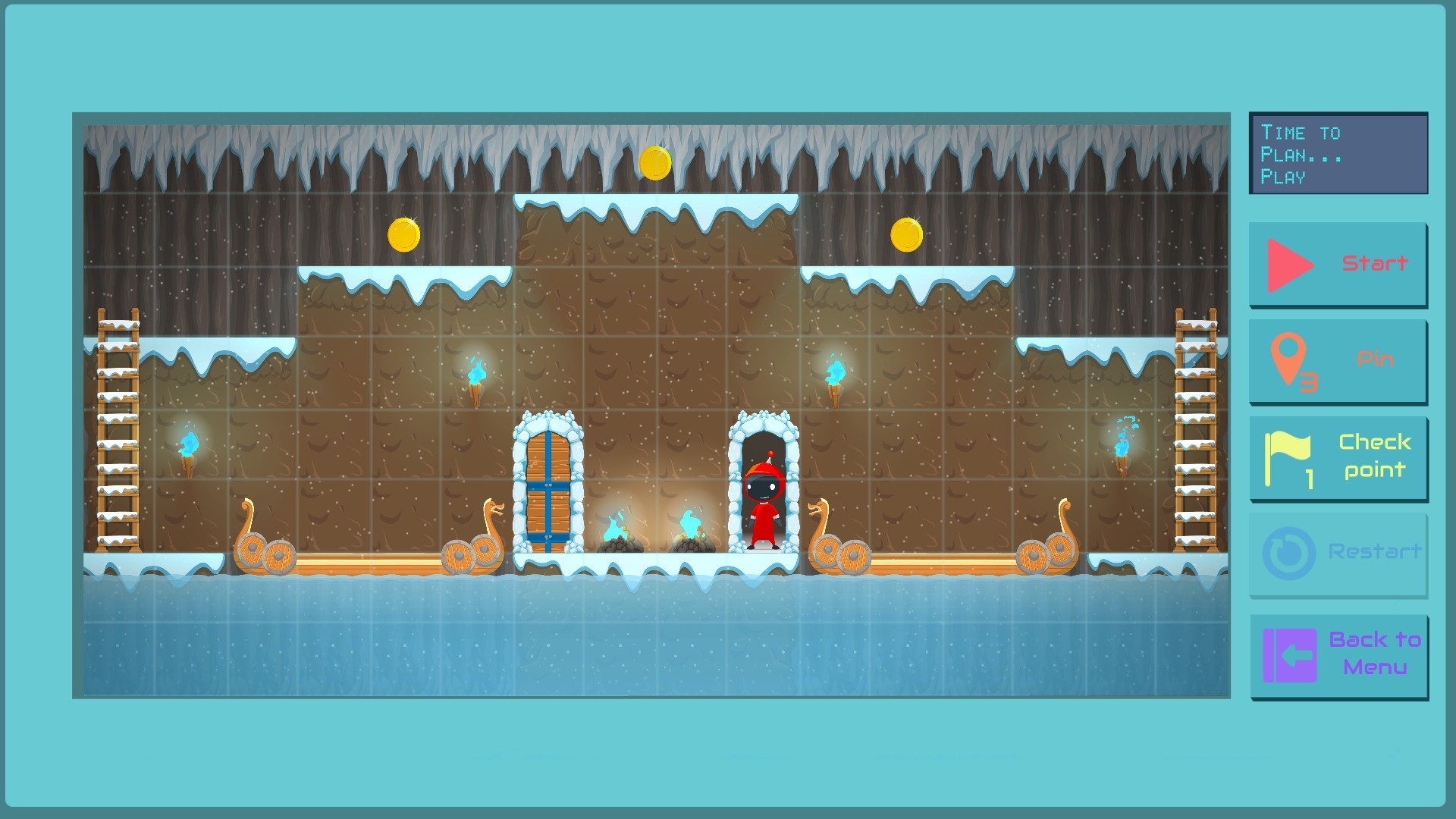

To make OS X memory analysis further difficult, Volatility doesn’t maintain a very up to date set of profiles for analysis (not to mention Apple has made it increasingly impossible to easily collect memory from any recent OS X releases). Pathfinder Mac Os, free pathfinder mac os software downloads. The Web Help Desk software for Mac OS X offers an industry leading web-based help desk software feature set that allows you to dynamically assign, track and fulfill all of your technical support trouble tickets and customer service requests with. As for Mac OS, Pathfinder: Kingmaker - Enhanced Edition requirements here start with OS X El Capitan operating system. Processor needs to be at least Intel Core i7-3610QE @ 2.30GHz. 4 GB of RAM is required. Your graphics card should be Intel HD Graphics 4000. Finally, the game needs 30 GB of free disk space.

- In OS X 10.5, to view available disk space on your drive (or partition), you had to either open Activity Monitor, or open an Inspector/Get Info window for your hard drive. In OS X 10.6, you can use Quick Look instead. Select the drive in the Finder, then press the Space Bar.

- Minimum: Windows OS: Windows 7 64-bit or newer Processor: Intel Celeron 1037U @ 1.80GHz Memory: 4 GB RAM Graphics: Intel HD Graphics 3000 Storage: 30 GB available space Sound Card: DirectX Compatible Sound Card Mac OS: OS X El Capitan Processor: Intel Core i7-3610QE @ 2.30GHz Memory: 4 GB RAM Graphics: Intel HD Graphics 4000 Storage: 30 GB available space Linux OS: Ubuntu 14.04 LTS.

10.6: Easily view available disk space 24 comments Create New Account

| Click here to return to the '10.6: Easily view available disk space' hint |

The following comments are owned by whoever posted them. This site is not responsible for what they say.

This functionality works in 10.5, it's not some great new discovery.

Also, the status bar at the bottom of Finder windows shows the available space for a volume, and has done for YEARS.

But not in QuickLook, as this hint is about.

Wrong. This hint does work in 10.5 with QuickLook. Typing this from a 12' PowerBook G4 running 10.5.8, and the 'QuickLook on hard drive' functionality is identical to my 17' MacBook Pro running 10.6.1.

Wrong. This hint does work in 10.5 with QuickLook.This hint doesn't work for me on 10.5.8 for drive icons on the Desktop. It does work if the drive is selected in the sidebar or in the Volumes folder. Could the hint be about desktop drive icons?

I think you're right, I just assumed it was about desktop items but I guess it doesn't actually say that. However, the hint is given for the purpose of viewing available disk space, and if you have a finder window open then you most likely do not need quick look to accomplish this since the space shows up in the windows (assuming the window is showing a folder on the drive in question.) I know that has already been mentioned here many times, I am just using this to support the argument that the hint is probably about desktop icons.

Free space is also always listed at the bottom of any finder window, assuming you've got the sidebar/window chrome showing...

Or: right-click the desktop, select Show View Options, check Show Item Info. Size and free space will be listed under volumes.

OR (since 10.4 as far as I know) click on the desktop, open the view options (cmd-J) and activate the checkbox 'show object info': So you will see the available disk space anytime below the volume name.

If you are going to click on the drive icon anyway, why not just right-click (control-click) and then choose 'Get Info' from the pop-up menu? You will see more info than Quick Look provides.

Because you also have to close the get info window afterwards. With this hint it's a simple (slow) double tap of the space bar.

Great find. I'm glad you noticed this.

Using Quicklook is much faster and easier than going through the bother of pressing Option-click, navigating to the Show Info item, then having to close the window again. Just clicking on the icon and pressing SPACE twice is far more efficient, especially if you're using a trackpad.

This is just what I was looking for to improve my workflow.

Erm, you're saying 'keyboard shortcuts is quicker than menus'. But there are already keyboard shortcuts available.

Tapping space twice is only barely quicker than Command-I, Command-W. Notice those keyboard shortcuts have been available right from the very start of Macintosh System.

To the poster of this tip, please ignore the mean comments. I liked this hint. To everyone who states a different way, thank you. But the hint is still valid. Most of the other way listed (aside from the status bar), take more steps then pressing the spacebar.

Even the status bar option takes more effort, as you have to open a finder window to do it. This works from the desktop.

Showing the item info on the desktop works well, so long as your icons are huge and so there's enough space.

Great hint. Thanks.

While you have the window open you can click on another drive and it will switch and show that drives info. Nice hint.

---

Working on Macs in a PC environment is like putting on fireworks for the blind. Any noise scares everyone and no one see the brilliance of your work.

Working on Macs in a PC environment is like putting on fireworks for the blind. Any noise scares everyone and no one see the brilliance of your work.

Yeah guys seriously, read the hint before commenting- I actually mention the other ways of finding disk space; so stop yapping.

Great hint. Yes, it worked in 10.5 also, but I never saw it hinted before.

I've already voiced my frustration several times with negative commenters (I affectionately call 'snobs') on this site as of late. Please please people just ignore them. They don't realize this isn't a contest, but rather a collective knowledgebase site. Even if it's not 'some great new discovery,' I love seeing it documented.

Snobs be gone.

I don't think anyone is being a snob — the reason I (and I presume many other members) love this site so much is the high quality of the information here. Whenever I see misinformation in a hint, I feel obliged to point it out so that Rob will hopefully add a correction to the hint (or at least readers of the hint will have a chance to be informed by the comments, assuming they read that far…). I've been reading the site for nearly a decade (has it really been around that long?) and it does seem like the quality of the hints has taken a distinct downward turn this last year or so.

This particular hint contains a lot of misinformation. The claim that the behavior is new to 10.6. The (implied) claim that the author has mentioned all the other ways to get the information (which they fell far short of doing, as is obvious from all the 'mean' comments). For such a short hint, it really packs a lot of misinformation punch!

All that being said, I acknowledge that a lot of the corrective comments could have been phrased more tactfully. I'd suggest the rudeness is just an emotional (possible subconscious) reaction to a perception of a recent flood of questionable hints on the site.

Rubbish! I agree the quality of (some of) the hints here has dropped, but this isn't an example of that. The ONLY misinformation in the hint is the idea that it's new to 10.6, which anyway I'd regard more as the editor's job to check for than the hinter's. While of course the hinter should strive to be as accurate as he can, he can normally only go by what he remembers of the previous version, as by definition he can't check now. The editors on the other hand have other resources to call upon, presumably.

There is no requirement whatsoever for any hinter to point out the alternative ways of achieving the same thing. He's not writing an OS X manual, he's pointing out one handy thing he's found that people might not have noticed. If others use other methods to do the same thing, great, and it's good if they list them in the comments, but the first reply in particular was stupid and unnecessary.

I know, lets get all the people who post convoluted ways to do things through Terminal include the much simpler UI methods in their hints shall we, before they're accepted? Who cares that some people may prefer to work that way, I don't, so will start to insult the hinter for daring to suggest I should.

I think the drop in 'quality' you've noticed has several causes. One, the volume of hints has increased significantly due to the popularity of the site and the OS, so robg can't test everything, and two, many more novices are feeling like they can contribute. Both of these are good things. I prefer to look at the hints not as 100% rock solid take it to the bank info, but rather as points of experimentation and discussion. The 'snobs' see it differently. They like to show their prowess by pointing out the flaws in other people's hints, and presume they know every possible thing about every possible thing, in every possible configuration, with every possible peripheral, etc etc. It's not what they say, but how they say it. Often rude and superior. They put the hinter on the defensive. I'm really getting sick of it. I've been reading and contributing to this site for over six years, and one thing has changed for sure, the quality of the commenters.

This hint is a great example. It's a fine hint, but not 100% accurate. I've never seen it here before, and so it's fair game. Who should test it? We, the readers! And we should report back in a professional and respectful manner. That's how we get all the facts, not by taunting and degrading.

And this perceived drop in quality is as all perceptions involving comparisons over larger time periods skewed by the biased nature of human memory. Humans tend to forget the bad things and remember the good things, that is how our psyche manages to make life bearable.

People, this is definitely new to 10.6, this was one of my biggest frustration in 10.5, and when I noticed that a lot of new stuff started showing up in QL windows (such as copyrights on apps) I decided to check HDs.

I've used Report and although its great, I've had better luck with WheresTheFreeSpace. It is Modeled after a PC application that is very popular called <a href='http://www.wheresthefreespace.com'>Treesize (but its for Mac).</a>

I hate right-clicking the drive and check 'Get Info'. I just got too many FireWire and network drives. Interestingly when I google today, I see a pretty cheap app in AppStore. It's called FreeSpace. It shows all my drives' empty spaces in the menu bar. The numbers are always just there. I can even eject all drives at once in the menu. Which I think it is a big missed-out from Apple.

'About This Computer' Mac OS 9.1 window showing the memory consumption of each open application and the system software itself.

Historically, the classic Mac OS used a form of memory management that has fallen out of favor in modern systems. Criticism of this approach was one of the key areas addressed by the change to Mac OS X.

The original problem for the engineers of the Macintosh was how to make optimum use of the 128 KB of RAM with which the machine was equipped, on Motorola 68000-based computer hardware that did not support virtual memory.[1] Since at that time the machine could only run one application program at a time, and there was no fixedsecondary storage, the engineers implemented a simple scheme which worked well with those particular constraints. That design choice did not scale well with the development of the machine, creating various difficulties for both programmers and users.

Fragmentation[edit]

The primary concern of the original engineers appears to have been fragmentation – that is, the repeated allocation and deallocation of memory through pointers leading to many small isolated areas of memory which cannot be used because they are too small, even though the total free memory may be sufficient to satisfy a particular request for memory. To solve this, Apple engineers used the concept of a relocatable handle, a reference to memory which allowed the actual data referred to be moved without invalidating the handle. Apple's scheme was simple – a handle was simply a pointer into a (non-relocatable) table of further pointers, which in turn pointed to the data.[2] If a memory request required compaction of memory, this was done and the table, called the master pointer block, was updated. The machine itself implemented two areas in memory available for this scheme – the system heap (used for the OS), and the application heap.[3] As long as only one application at a time was run, the system worked well. Since the entire application heap was dissolved when the application quit, fragmentation was minimized.

The memory management system had weaknesses; the system heap was not protected from errant applications, as would have been possible if the system architecture had supported memory protection, and this was frequently the cause of system problems and crashes.[4] In addition, the handle-based approach also opened up a source of programming errors, where pointers to data within such relocatable blocks could not be guaranteed to remain valid across calls that might cause memory to move. This was a real problem for almost every system API that existed. Because of the transparency of system-owned data structures at the time, the APIs could do little to solve this. Thus the onus was on the programmer not to create such pointers, or at least manage them very carefully by dereferencing all handles after every such API call. Since many programmers were not generally familiar with this approach, early Mac programs suffered frequently from faults arising from this.[5]

Palm OS and 16-bit Windows use a similar scheme for memory management, but the Palm and Windows versions make programmer error more difficult. For instance, in Mac OS, to convert a handle to a pointer, a program just de-references the handle directly, but if the handle is not locked, the pointer can become invalid quickly. Calls to lock and unlock handles are not balanced; ten calls to HLock are undone by a single call to HUnlock.[6] In Palm OS and Windows, handles are an opaque type and must be de-referenced with MemHandleLock on Palm OS or Global/LocalLock on Windows. When a Palm or Windows application is finished with a handle, it calls MemHandleUnlock or Global/LocalUnlock. Palm OS and Windows keep a lock count for blocks; after three calls to MemHandleLock, a block will only become unlocked after three calls to MemHandleUnlock.

Addressing the problem of nested locks and unlocks can be straightforward (although tedious) by employing various methods, but these intrude upon the readability of the associated code block and require awareness and discipline on the part of the coder.

Memory leaks and stale references[edit]

Awareness and discipline are also necessary to avoid memory 'leaks' (failure to deallocate within the scope of the allocation) and to avoid references to stale handles after release (which usually resulted in a hard crash—annoying on a single-tasking system, potentially disastrous if other programs are running).

Switcher[edit]

The situation worsened with the advent of Switcher, which was a way for a Mac with 512KB or more of memory to run multiple applications at once.[7] This was a necessary step forward for users, who found the one-app-at-a-time approach very limiting. Because Apple was now committed to its memory management model, as well as compatibility with existing applications, it was forced to adopt a scheme where each application was allocated its own heap from the available RAM.[8]The amount of actual RAM allocated to each heap was set by a value coded into the metadata of each application, set by the programmer. Sometimes this value wasn't enough for particular kinds of work, so the value setting had to be exposed to the user to allow them to tweak the heap size to suit their own requirements. While popular among 'power users', this exposure of a technical implementation detail was against the grain of the Mac user philosophy. Apart from exposing users to esoteric technicalities, it was inefficient, since an application would be made to grab all of its allotted RAM, even if it left most of it subsequently unused. Another application might be memory starved, but would be unable to utilize the free memory 'owned' by another application.[3]

While an application could not beneficially utilize a sister application's heap, it could certainly destroy it, typically by inadvertently writing to a nonsense address. An application accidentally treating a fragment of text or image, or an unassigned location as a pointer could easily overwrite the code or data of other applications or even the OS, leaving 'lurkers' even after the program was exited. Such problems could be extremely difficult to analyze and correct.

Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os X

Switcher evolved into MultiFinder in System 4.2, which became the Process Manager in System 7, and by then the scheme was long entrenched. Apple made some attempts to work around the obvious limitations – temporary memory was one, where an application could 'borrow' free RAM that lay outside of its heap for short periods, but this was unpopular with programmers so it largely failed to solve the problems. Apple's System 7 Tune-up addon added a 'minimum' memory size and a 'preferred' size—if the preferred amount of memory was not available, the program could launch in the minimum space, possibly with reduced functionality. This was incorporated into the standard OS starting with System 7.1, but still did not address the root problem.[9]

Virtual memory schemes, which made more memory available by paging unused portions of memory to disk, were made available by third-party utilities like Connectix Virtual, and then by Apple in System 7. This increased Macintosh memory capacity at a performance cost, but did not add protected memory or prevent the memory manager's heap compaction that would invalidate some pointers.

32-bit clean[edit]

Originally the Macintosh had 128 kB of RAM, with a limit of 512 kB. This was increased to 4 MB upon the introduction of the Macintosh Plus. These Macintosh computers used the 68000 CPU, a 32-bit processor, but only had 24 physical address lines. The 24 lines allowed the processor to address up to 16 MB of memory (224 bytes), which was seen as a sufficient amount at the time. The RAM limit in the Macintosh design was 4 MB of RAM and 4 MB of ROM, because of the structure of the memory map.[10] This was fixed by changing the memory map with the Macintosh II and the Macintosh Portable, allowing up to 8 MB of RAM.

Because memory was a scarce resource, the authors of the Mac OS decided to take advantage of the unused byte in each address. The original Memory Manager (up until the advent of System 7) placed flags in the high 8 bits of each 32-bit pointer and handle. Each address contained flags such as 'locked', 'purgeable', or 'resource', which were stored in the master pointer table. When used as an actual address, these flags were masked off and ignored by the CPU.[4]

While a good use of very limited RAM space, this design caused problems when Apple introduced the Macintosh II, which used the 32-bit Motorola 68020 CPU. The 68020 had 32 physical address lines which could address up to 4 GB (232 bytes) of memory. The flags that the Memory Manager stored in the high byte of each pointer and handle were significant now, and could lead to addressing errors.

In theory, the architects of the Macintosh system software were free to change the 'flags in the high byte' scheme to avoid this problem, and they did. For example, on the Macintosh IIci and later machines, HLock() and other APIs were rewritten to implement handle locking in a way other than flagging the high bits of handles. But many Macintosh application programmers and a great deal of the Macintosh system software code itself accessed the flags directly rather than using the APIs, such as HLock(), which had been provided to manipulate them. By doing this they rendered their applications incompatible with true 32-bit addressing, and this became known as not being '32-bit clean'.

Mac Os Catalina

In order to stop continual system crashes caused by this issue, System 6 and earlier running on a 68020 or a 68030 would force the machine into 24-bit mode, and would only recognize and address the first 8 megabytes of RAM, an obvious flaw in machines whose hardware was wired to accept up to 128 MB RAM – and whose product literature advertised this capability. With System 7, the Mac system software was finally made 32-bit clean, but there were still the problem of dirty ROMs. The problem was that the decision to use 24-bit or 32-bit addressing has to be made very early in the boot process, when the ROM routines initialized the Memory Manager to set up a basic Mac environment where NuBus ROMs and disk drivers are loaded and executed. Older ROMs did not have any 32-bit Memory Manager support and so was not possible to boot into 32-bit mode. Surprisingly, the first solution to this flaw was published by software utility company Connectix, whose 1991 product MODE32 reinitialized the Memory Manager and repeated early parts of the Mac boot process, allowing the system to boot into 32-bit mode and enabling the use of all the RAM in the machine. Apple licensed the software from Connectix later in 1991 and distributed it for free. The Macintosh IIci and later Motorola based Macintosh computers had 32-bit clean ROMs.

Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os Catalina

It was quite a while before applications were updated to remove all 24-bit dependencies, and System 7 provided a way to switch back to 24-bit mode if application incompatibilities were found.[3] By the time of migration to the PowerPC and System 7.1.2, 32-bit cleanliness was mandatory for creating native applications and even later Motorola 68040 based Macs could not support 24-bit mode.[6][11]

Object orientation[edit]

Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os 8

The rise of object-oriented languages for programming the Mac – first Object Pascal, then later C++ – also caused problems for the memory model adopted. At first, it would seem natural that objects would be implemented via handles, to gain the advantage of being relocatable. These languages, as they were originally designed, used pointers for objects, which would lead to fragmentation issues. A solution, implemented by the THINK (later Symantec) compilers, was to use Handles internally for objects, but use a pointer syntax to access them. This seemed a good idea at first, but soon deep problems emerged, since programmers could not tell whether they were dealing with a relocatable or fixed block, and so had no way to know whether to take on the task of locking objects or not. Needless to say this led to huge numbers of bugs and problems with these early object implementations. Later compilers did not attempt to do this, but used real pointers, often implementing their own memory allocation schemes to work around the Mac OS memory model.

While the Mac OS memory model, with all its inherent problems, remained this way right through to Mac OS 9, due to severe application compatibility constraints, the increasing availability of cheap RAM meant that by and large most users could upgrade their way out of a corner. The memory was not used efficiently, but it was abundant enough that the issue never became critical. This is ironic given that the purpose of the original design was to maximise the use of very limited amounts of memory. Mac OS X finally did away with the whole scheme, implementing a modern sparse virtual memory scheme. A subset of the older memory model APIs still exists for compatibility as part of Carbon, but maps to the modern memory manager (a thread-safe malloc implementation) underneath.[6] Apple recommends that Mac OS X code use malloc and free 'almost exclusively'.[12]

Pathfinders: Memories Mac Os Download

References[edit]

- ^Hertzfeld, Andy (September 1983), The Original Macintosh: We're Not Hackers!, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Hertzfeld, Andy (January 1982), The Original Macintosh: Hungarian, archived from the original on June 19, 2010, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abcmemorymanagement.org (December 15, 2000), Memory management in Mac OS, archived from the original on May 16, 2010, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abHertzfeld, Andy, The Original Macintosh: Mea Culpa, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Apple Computer (October 1, 1985), Technical Note OV09: Debugging With PurgeMem and CompactMem, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^ abcLegacy Memory Manager Reference, Apple Inc., June 27, 2007, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Hertzfeld, Andy (October 1984), The Original Macintosh: Switcher, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Mindfire Solutions (March 6, 2002), Memory Management in Mac OS(PDF), p. 2, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^'System 7.1 upgrade guide'(PDF). Archived from the original(PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^'memory maps'. Osdata.com. March 28, 2001. Retrieved May 11, 2010.CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Apple Computer (January 1, 1991), Technical Note ME13: Memory Manager Compatibility, retrieved May 10, 2010CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

- ^Memory Allocation Recommendations on OS X, Apple Inc, July 12, 2005, retrieved September 22, 2009CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

External links[edit]

- Macintosh: ROM Size for Various Models, Apple Inc, August 23, 2000, retrieved September 22, 2009CS1 maint: discouraged parameter (link)

Retrieved from 'https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Classic_Mac_OS_memory_management&oldid=1008965847'